India is a conglomerate of several states with multiple regional dialects. And, we have our identity as Indians, also a linguistic identity based on our mother tongue or region of birth. Together with castes and religions, these two identities have been co-existing in our country simultaneously.

It would be a blunt lie if someone said that co-existence had been smooth. There have been frictions. There are frictions now as well, stoked by politicians and overeager citizens. They want to single out one of these identities and push it to fanatic levels. In this case, those for and those against Hindi.

Those asking for Hindi as the link language between states trying to establish a national identity by discrediting regional uniqueness will only achieve an artificial sense of nationalism. It is unwarranted and will only work against the concept of one nation.

At the same time, the so-called protectors of regional/linguistic/religious/caste identities fielding them above our notion of the nation are—to be honest—fostering separatist tendencies. It’s an apparent truth that regional political parties have used linguistic fanaticism as a tool to keep national parties at bay.

We have these two distinct political standpoints on what should be our national language or the least, a common language between states. Both are polarising.

National parties like the BJP and Congress have originated from Hindi-speaking northern states of the country. They have held the idea that Hindi is the most widely spoken language in the country, hence should be the national language or the link language of states. For the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, mooting Hindi as the national language is a part of their ideological agenda.

They must understand that choosing a language does not work like electoral democracy, where the majority wins. In electoral democracy, though the majority wins, there is representation from all others. How can we apply that to selecting a national/link language?

Now, let’s look at the other side, the regional parties willing to embrace English for Hindi. If the union government attempted to push Hindi, they would call it an imposition but have no qualms about accepting the language of the oppressive colonial British. So when these parties object by saying, “English is okay but not Hindi,” it shows their hypocrisy.

If they care so much for their regional language, they will stop English medium schools. Will they? They won’t. If they did that, their state people would vote them out of power, and they know it. People want their children to learn English—some even want them to learn Hindi—to enhance their educational and career prospects within India and in foreign lands.

So the scream of those for and those against Hindi is a political ploy louder than a composed rational citizen’s voice. Both sides have used them for their electoral gains triggering linguistic sentiments in people. And let’s not doubt it. On the language issue, no prudent and unifying solution would come from both.

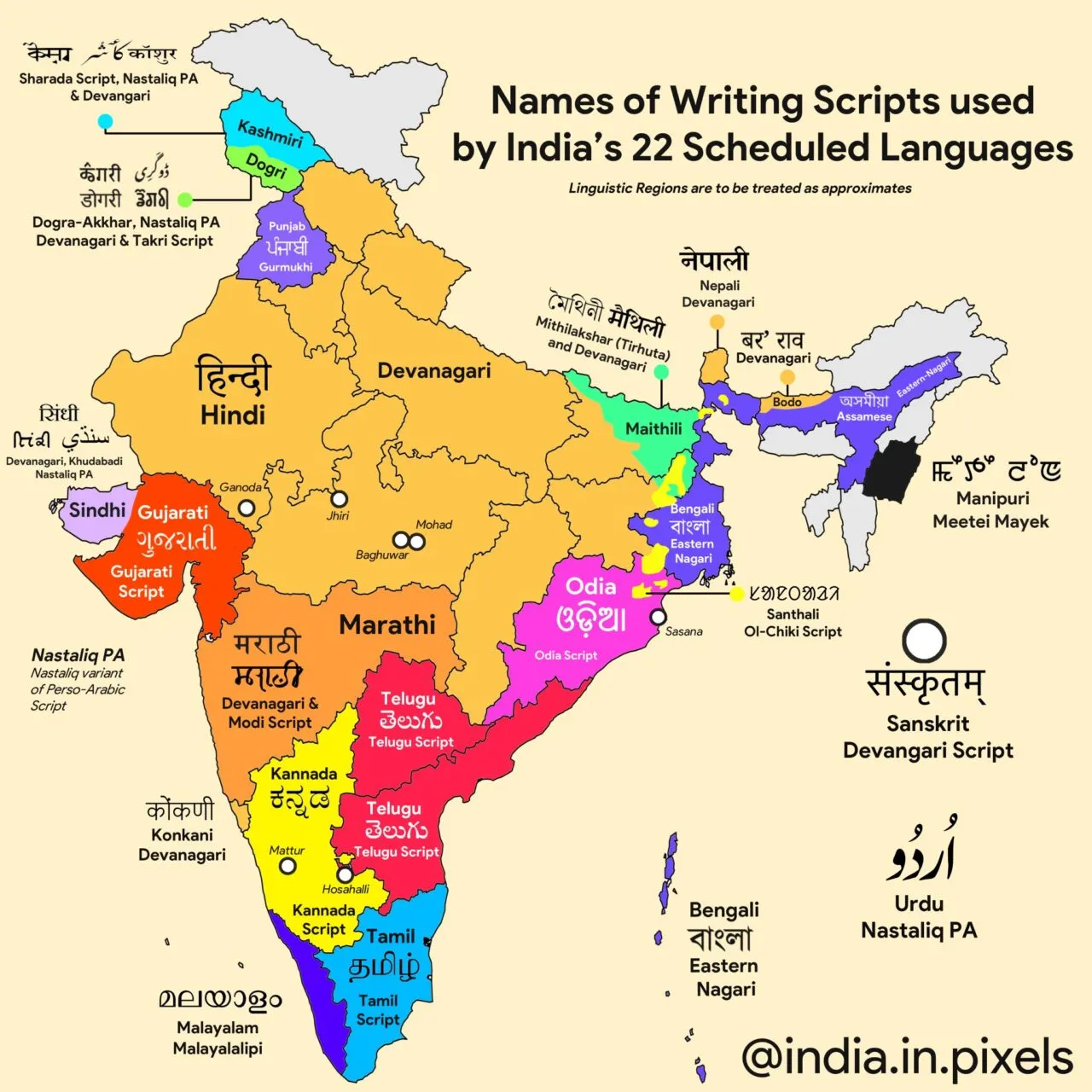

According to Censusindia.gov.in Indians speak a total of 121 languages and 270 mother tongues. There are 22 languages specified in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India.

Watch the column for what can solve India’s language problem and the difference between center and states.

Image Source: Twitter/Indiainpixels